History of the Mint

HISTORY OF SEGOVIA’S MINTS

Coins are an industrially manufactured product, each piece identical, made in series to exact specifications regarding weight, fineness and objects portrayed, issued by governments in their own benefit. Coinage is curiously one of civilization’s oldest, most ingenious and useful inventions. Coins were first used in Lidia, on the coast of Turkey, around 640 B.C. By the end of the 4th century B.C. the Greeks were striking coins in their Iberian costal colonies of Ampurias, Rosas, Ibiza and Cadiz. Later, the Romans struck coins in more than 300 mints, flooding the peninsula with coinage. Coins are not only useful to promote colonization and commerce, but also as a political statement, omnipresent symbol of the colony; the Roman occupation of the peninsula.

The two thousand year tradition of striking coins in Segovia has its roots between 30 and 20 B.C. when the bronze Roman ‘as’ was struck. The famous Iberian knight on horseback above the inscription ‘SEGOVIA’ is the oldest known source of the name of the city. It’s even possible that these coins were used to pay the builders of the aqueduct.

The period of Roman influence in Iberia began to decline, and in 408 A.C. the peninsula was invaded by the Suebi, Alans and Vandals. Later, from 509 to 710 the Visigoths struck coins in nearly 80 mints, but no coins are known to be from Segovia during these periods. Then, from 711 to the end of the Reconquest in 1492, the Muslim invaders struck coins in more than 60 different mints. But again, no coins issued by Muslim authorities are known to be from Segovia.

MINTING IN UNCONFIRMED LOCATIONS

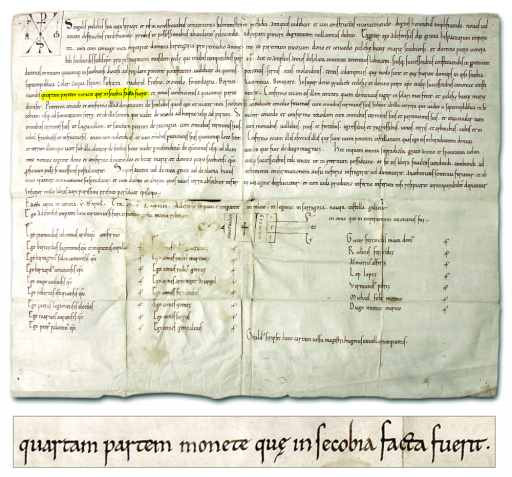

During the period of the Reconquest, many coins were issued by the Christian kings in Segovia. The earliest identified pieces are from the time of Alfonso VI of Castile (1072-1109). Later, Alfonso VII (1126-1157) also struck billon coins in Segovia as well as leaving us the first written testimony of the coining industry in Segovia. In 1135 he granted the church of Saint Mary, one-third part of all the coins struck in Segovia, reducing it to the one-fourth part in 1139, for the costs of building the new cathedral.

Bronze Roman ‘as’, the oldest known example of the name of Segovia (30-20 a.C.).

Medieval coins struck at unknown locations in Segovia.

Alfonso VII in 1139, grants one quarter part of the coins struck in Segovia for the construction of the cathedral.

Segovia became populous and prospered. Even today, over 20 Romanesque churches from the medieval period are still standing in Segovia, proof of the economic activity which gave rise to the striking of abundant coinage. These issues were all struck in unconfirmed minting locations, probably beginning in a small smithy within the cathedral, which was being built with the coins being struck. These coins include billon issues by Alfonso VIII (1158-1214), Henry II, (1369-1379) and John I (1379-1390). It has not yet been shown that Henry III (1390-1406) or John II (1406-1454), who was the father of Henry IV, struck coins in Segovia.

THE OLD HAMMER MINT

Henry IV, known as the Segovian King because he lived in this city, built a new Mint, which he inaugurated in 1455. According to Diego de Colmenares, in his “History of Segovia”, published in 1637, Henry IV “ordered the Mint standing today to be built” because “the Mint was in a bad state of repair”. Seemingly, coining began in the cathedral and perhaps at a later time moved to the location where Henry IV built his new Mint.

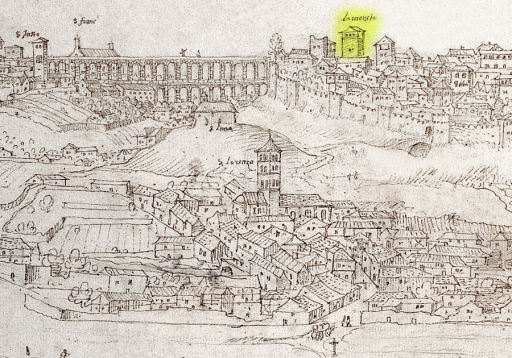

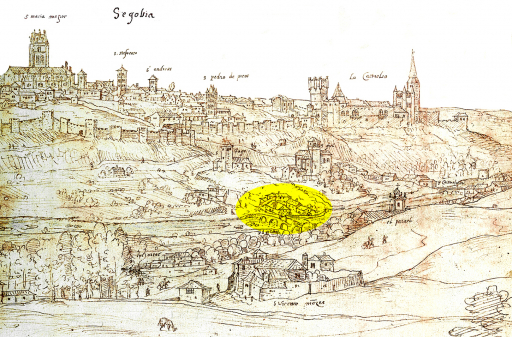

The new factory was located in the yard of the Saint Sebastian church, along the inside wall of the city, and equidistant between the Saint John gate to the city and the end of the Aqueduct. For more than a century it was know as the “Segovia Mint”. But with the construction of the new Royal Mill Mint in 1583, Henry IV’s factory became known as the “Old Mint”, and figures as such in all official documents since then in order to avoid confusion, since both mints functioned simultaneously during 95 years.

Henry IV’s old hammer Mint, “LA MONETA”, as seen in the drawing by Wyngaerde, 1562.

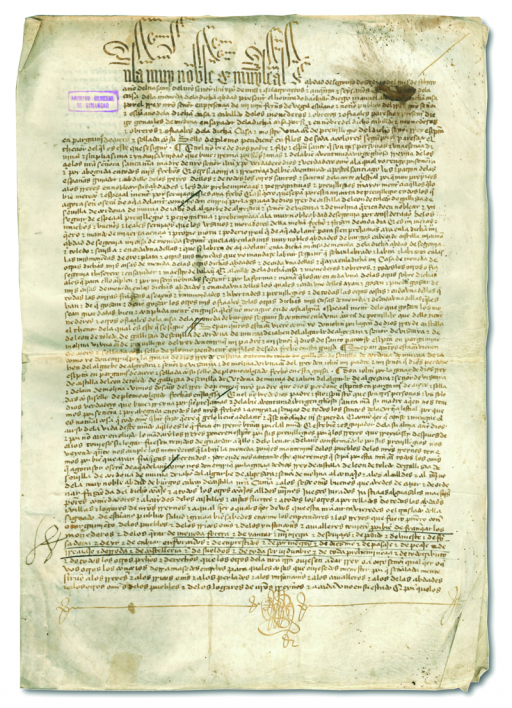

Henry IV grants special privileges to his coiners in 1456.

The Old Mint struck great quantities of coins, from the most famous and giant coins of Castile, to tons of the most common issues. In 1619 work was carried out on the building in order to increase production, which in 1625 alone reached over 400 tons of copper coin struck in one year, or over a ton of metal per day. We can imagine the amount of charcoal it would take to melt that much copper daily. There would have been a constant parade of pack mules coming and going, carrying fuel, copper, struck coins, provisions; as well as many people, over one hundred coiners alone with hammers, not counting the rest of the crew and officials. In reality, it was one huge industrial plant within the walls of the city.

The glory days for the Old Mint lasted until 1626, when the series of copper coins being struck at all the mints, was suspended. From then on, coining was very sporadic, except for six big campaigns in which countermarks were hammered onto old copper coins to adjust their value. The plant fell into total disuse after 1661. In 1680 the Old Mint opened again to strike its last coins, and finally closed its doors for the last time on June 8, 1681. In 1686 Charles II ordered that no more hammer striking of coins would be allowed, which sealed the fate of the Old Mint, although it did not loose its minting privilege until 1730.

20 golden enriques, ostentation coin of the so called ‘Segovian King’.

20 excelentes of Ferdinand and Isabella, symbol of their power.

The last coin struck at the old hammer Mint.

GENERAL CONTEXT

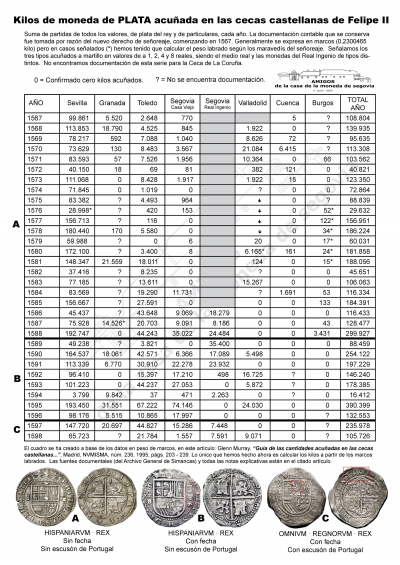

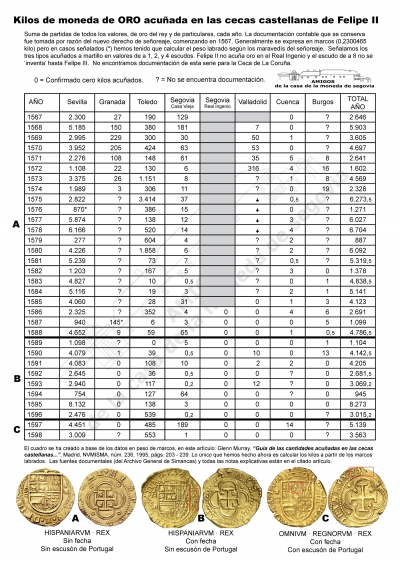

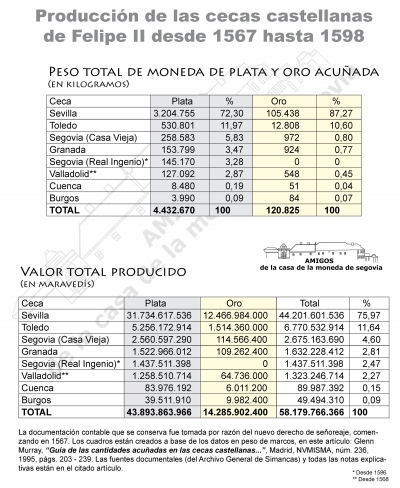

A fundamental part of understanding the history of the two Segovia Mints is that of considering the context of Castilian mints in general; a reality to which both mints were always subjected. Starting with King Philip II, the situation was very competitive, and each mint vied against the others to attract business of the silver merchants as well as the king. The silver arrived once a year to Seville on the galleons from Havana. The first to strike coins was the king, who prohibited the merchants from coining their silver in Seville until his bars were all converted into coin. Philip II wanted cash in hand as quickly as possible in order to avoid paying interest on his many and very famous debts. When the King occupied the Seville Mint for his own purposes, the silver merchants were literally forced to take their metals to other mints for coining, signing prearranged written agreements with officials of the mint, and using slow and expensive mule-trains to transport the metal, and later coins.

As a result of this situation and the extra costs involved for transporting the metal, the silver merchants, scheming with mint officials, began helping themselves to what they could by illegally reducing the fineness and weight of the coins they struck. A typical shipment of 35.000 kilos of silver to Segovia required: 700 mules (50 kilos / mule), 150 people (100 mule drivers + 25 security guards + 25 helpers), as well as food for people and mules during 30 days (600 km at 20 km / day). There were mints in Seville, Granada, Cuenca, Toledo, Segovia, Burgos and La Coruña. In 1568 Philip II established a new mint in Valladolid, and later his private Royal Mill Mint in Segovia, which began striking his own silver in 1586. Madrid would not have a mint until 1614. The volume of coins struck in each mint is typically a direct result of its distance from Seville, which is why practically no coins are known during this period from La Coruña.

Chart of silver coins struck.

Chart of Gold coins struck.

Proportions struck by each mint.

THE ROYAL MILL MINT

The Royal Mill Mint, is without a doubt, the most exceptional of all the Spanish Mints, peninsular as well as Ultramar. Designed, built and administered as private property of the king, it was managed by the Junta de Obras y Bosques, which ran all of the palaces and royal sites, while all the other mints were run by Hacienda, or the Treasury. Unique is its history, its vanguard technology and the fame it enjoyed. It was a complex, modern departmentalized industrial plant, designed by Juan de Herrera and a team of German technicians, for the mechanical in series production of a sophisticated, high-precision product, a full two centuries before the Industrial Revolution. Today it is known as the oldest, most advanced and complete example of a true industrial factory, still standing.

Tyrolean coin compared to a Spanish coin of the same period. The difference was astounding.

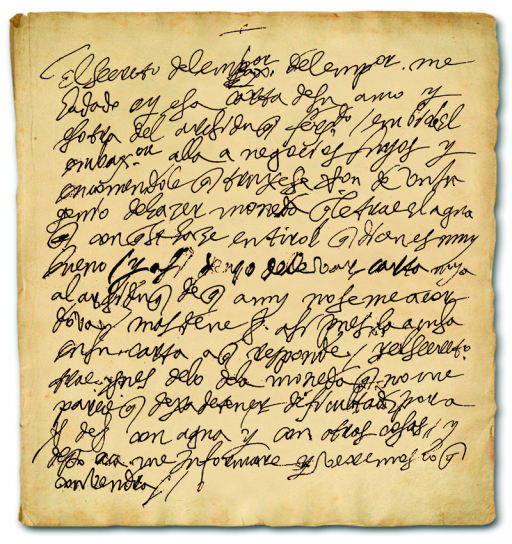

Handwritten note by Phillip II in June of 1581 regarding the installation of coining machines in Spain.

The old paper mill which Phillip II will later purchase as the location for his new mint, in a drawing by Wyngaerde, 1562.

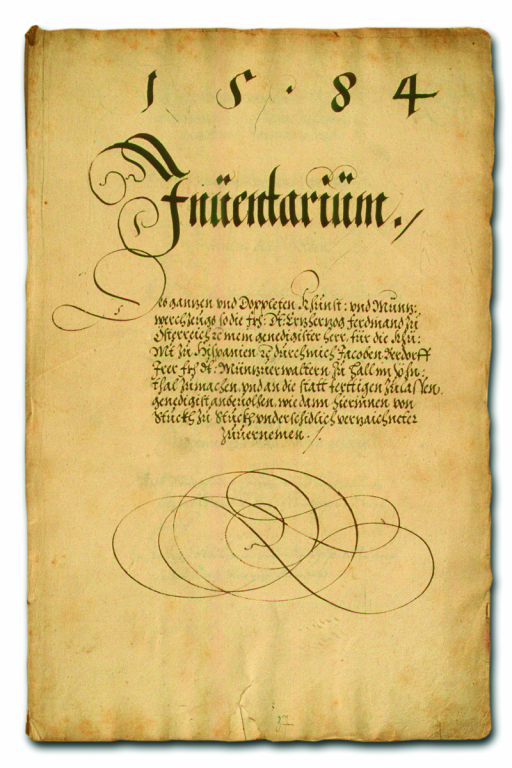

Inventory of the machinery brought to Segovia from the Mint at Hall in Tyrol.

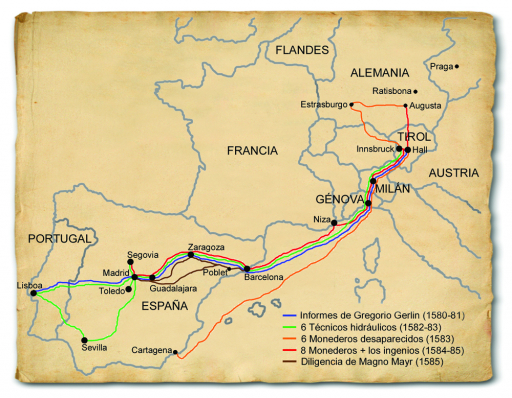

The major trips made in order to establish the new mechanized mint in Segovia.

The first coin rolled off the mill at the new Mint is also the first Spanish coin to carry a date.

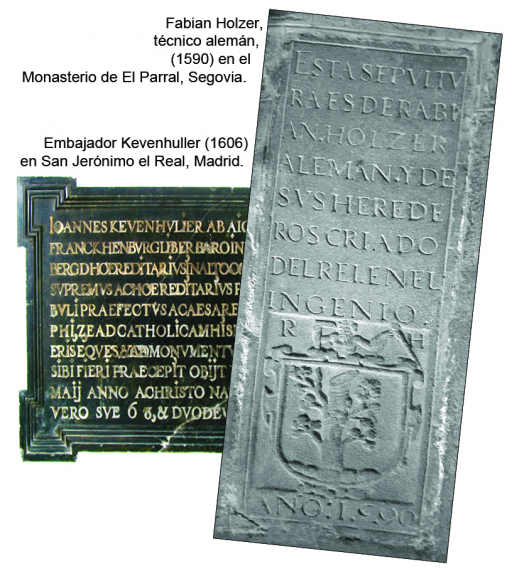

Roller-die coining on laminating mills was invented in Germany in 1551. Just around that time, huge shipments of silver began arriving from the Indies to Seville, and the rush to hammer strike all that silver into coinage led to sloppy work and irregular shaped coins. The dynastic contacts of Phillip II, led to an agreement with his cousin, the Archduke of Tyrol, in Innsbruck, to implement mechanical coining in Spain, for the purpose of improving coin quality, making it harder to clip irregular coins once they left the mint. The negotiations began in 1581 with several trips being made, the last in 1584, when the industrial convoy of 25 large loads left the Hall in Tyrol Mint, heading for Segovia, nearly 2.000 kms away, in a trip which took eight months and had grave difficulties. This convoy is thought today to have been the most sophisticated industrial transfer of technology ever undertaken until then, over the longest distance.

Phillip II ordered that no assayer mark be put on the coins from his Royal Mill Mint (4 coins on left), although the next kings immediately ordered its use (3 coins on right).

Coin with special decorative border struck during the visit of Phillip II to the Mint in 1587.

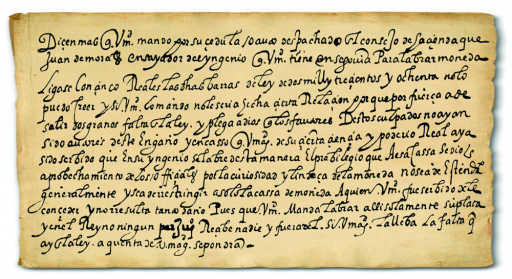

Phillip II’s chief justice, scolds the king in October of 1588 after discovering his fraud at the Mint.

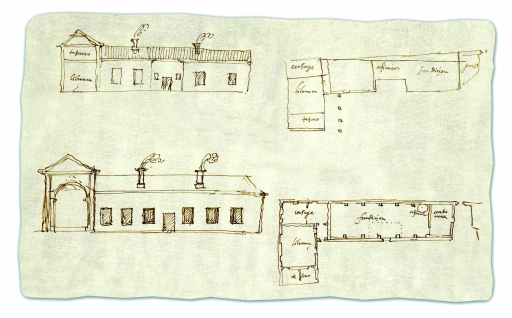

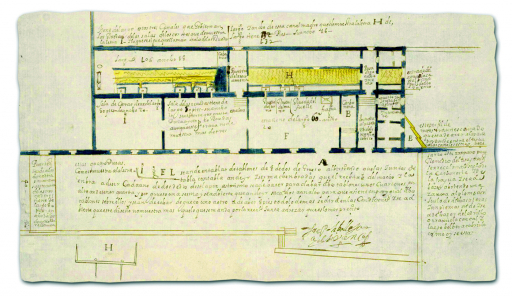

Plans of the upper patio building, for repairs after a fire in 1607.

The spectacular 50-real, and 100 and 8-escudo pieces, invented at, and exclusively made by, the Royal Mill Mint.

Roller dies for coining on a laminating mill.

The Royal Mill Mint produced coins from 1586 to 1869. It was the famous Spanish mint of first reference even from before the day of its opening, through all of the 17th century. But after 1700, with the installation of screw presses in the Madrid and Seville Mints, the Royal Mill began loosing its importance. In 1730 Phillip V ordered that in the future, only the Madrid and Seville Mints could strike silver and gold coins. Segovia, thus, was relegated to the production of copper coins, although during many years it was able to maintain the exclusive right among all the mints, to strike copper issues. The prohibition of striking silver and gold, though, meant little to the workers, who were paid according to how much metal they struck into coin, by weight. They were more interested in having consistent and stable work year round, in spite of the metal being struck.

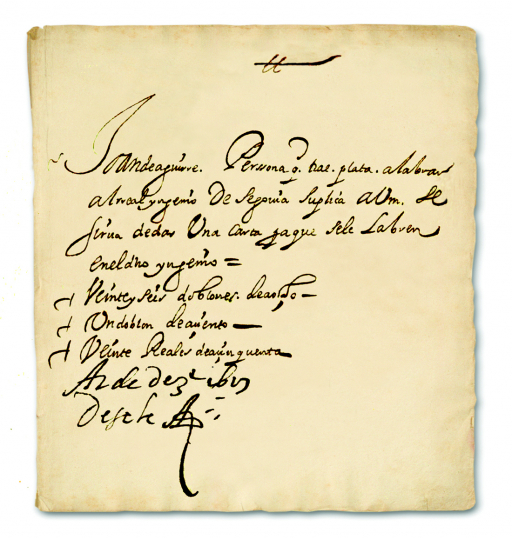

Petition dated 1617, for Juan de Aguirre, silver merchant from Seville, to produce cincuentines, centenes and 8-escudo pieces.

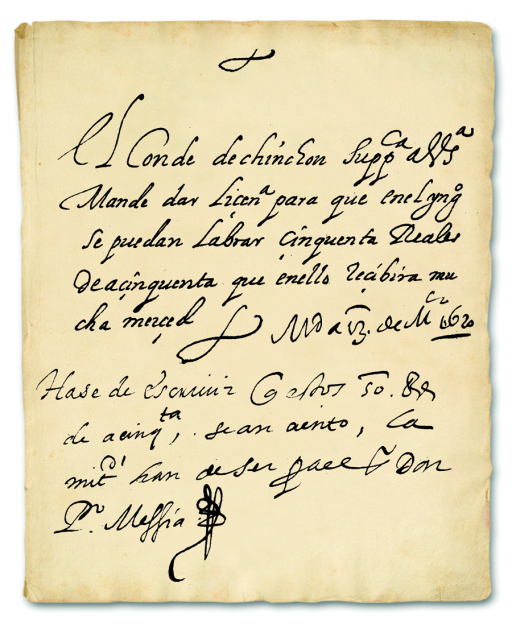

Petition dated 1620, for the Count of Chinchon, to produce cincuentines.

Copper coins from each of the two Segovia Mints. The difference between the technologies used is evident.

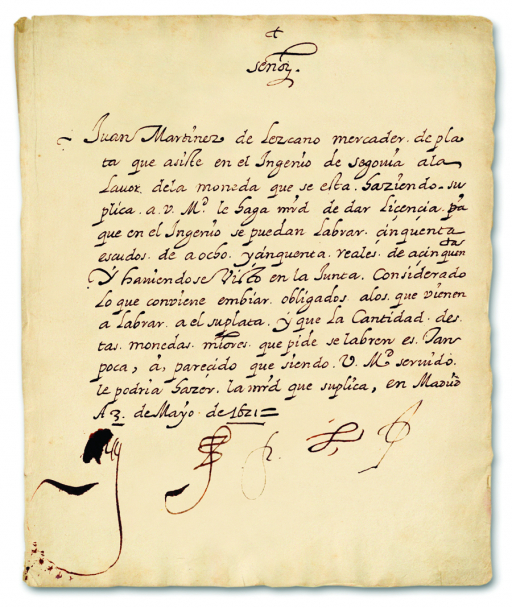

Petition dated 1621, for Juan Martinez de Lezcano, silver merchant from Seville, to produce cincuentines and 8-escudo pieces.

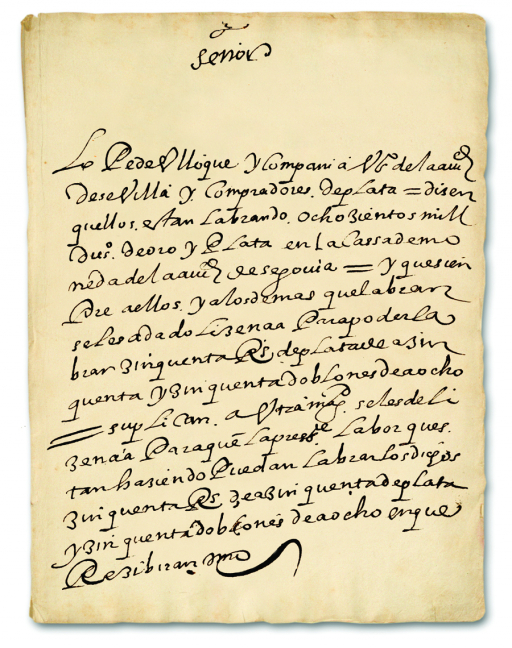

Petition dated 1630, for Lope de Ulloque, silver merchant from Seville, to produce cincuentines and 8-escudo pieces.

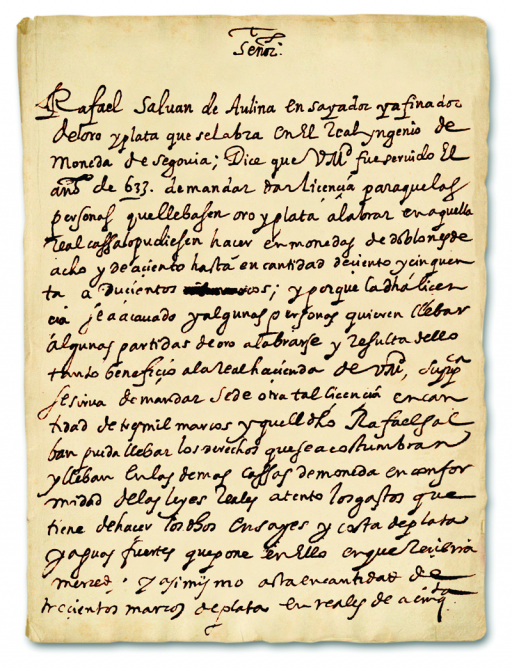

Petition dated 1633, for Rafael Salban, assayer, to renew his license for producing centenes and 8-escudo pieces from contraband gold for private individuals.

The Royal Mill had periods of great activity, and others of none at all. The erratic activity levels led to long periods in which the Mint was abandoned, and putting it back on line again usually required extensive repair work. The Mint never had a consistent and stable supply of metal to strike until the new series of copper coins of 1772 was begun. In order to produce those coins, the factory was reconverted to operate with screw presses.

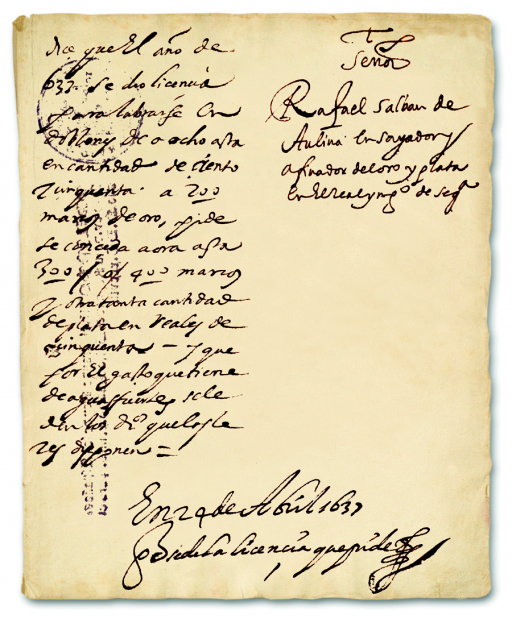

Autorization dated 1637 for the assayer to produce gold coins for private individuals without questioning the origin of the gold.

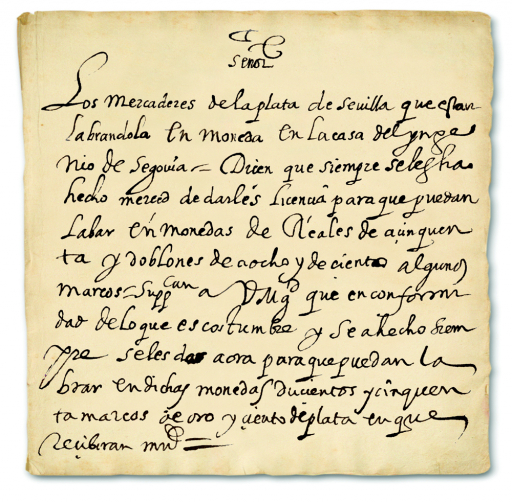

Petition dated 1659 for Juan Cruz de Gainza and Pedro de Azpilicueta, silver merchants from Seville, to produce cincuentines, centenes and 8-escudo pieces.

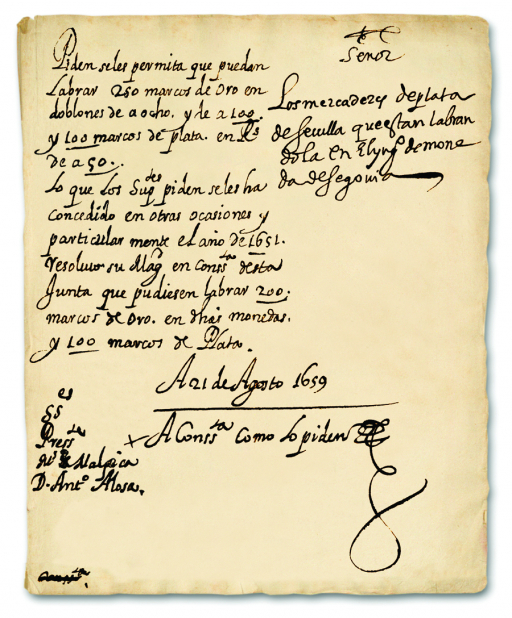

Autorization dated 1659, to produce cincuentines, centenes and 8-escudo pieces.

Plan of the machinery room at the Mill Mint in 1678, drawn for making repairs.

Coins struck in Segovia by Joseph Napoleon, from 1810 to 1813.

Proclamation medals of the declaration of the Constitution in Segovia, in 1812.

The most famous coins of the Royal Mill are also the crown jewels of Spanish monetary history: the giant cincuentines (50-real silver) and centenes (100-escudo gold), both 76 mm in diameter. These spectacular pieces were invented in 1609 by the Mill’s chief engraver, Diego de Astor, a 24 year old immigrant from Flanders. They were only permitted to be struck (rolled) with written permission from the king himself, and only at his Mill, no other mint. The first 8 escudo gold pieces ever issued were also produced starting then, on roller dies also engraved by Astor. Written permission was also required to mint them, but after 1631 other mints were also allowed to strike 8 escudo pieces.

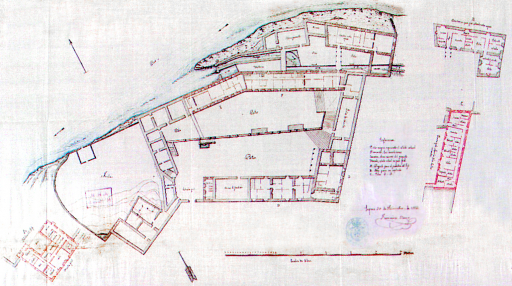

Plan dated 1861 of the entire Mint complex, for making repairs and additions.

The last piece struck in Segovia is this medallic-coin commemorating the Revolution of September, or “The Glorious”, in 1868.

Grave stones one can visit today, of the protagonists who brought the coining machines to Spain.

In 1855 Isabel II approved a project to centralize all Spanish coin production in Madrid, and close all the other mints. The huge new mint, which occupied all of today’s Plaza Colon, was built on credit against the future closure and sale of the other mints. The new steam engine driven factory with automatic presses was opened in 1861, and the Royal Mill in Segovia was closed in February of 1869. Finally, after six unsuccessful attempts to auction the Mint, it was awarded to the only bidder in 1878, who converted the building into a flour mill. The third owner of the flour mill closed his business in 1968 and abandoned the site. In 1989, Segovia City Hall acquired the entire complex by means of expropriation. From 2007 to 2011 the entire monument was restored and in 2012 the Museum of the Royal Mill Mint was opened.

(To learn more, see the .pdf and the bibliography)

HISTORY OF SEGOVIA MINTS

In this section we cover the history of the Mints in Segovia, paying special attention to their different locations and plans of the buildings, as well as the technologies employed for coining. Included is an interesting debate about why coining with a screw press is more efficient than using roller dies, which occurred during the reconversion of the Mint in 1771.

PDF Index

MINTS OF UNCERTAIN LOCATION (antes de 1455)

THE OLD HAMMER MINT (1455-1681)

THE ROYAL MILL MINT (1583-1869)